Every now and then, someone calls me asking how to find a shaman or a medicine man or woman. I try to be of assistance, yet those who truly possess these capabilities are rare in our time. That rarity is why discernment matters—and why I’m writing this.

From early childhood, I was drawn to Native Americans, and when I learned about the traditional doctors—medicine men and women—the vision quest, and the visionary experiences and powers they carried, I decided that if ever given the opportunity, this is what I would do with my life. At seventeen, I took off on my own and made it as far as Oklahoma, where I landed in a community of Kiowa Indians. From the time I arrived, I immersed myself in the community and culture—taking part in powwows and sitting up all night in peyote meetings with the elders. It was in one of these meetings that I first met my mentor, Horace Daukei.

When I was first introduced to Horace, he didn’t have much to say. He tended to be very introspective after the peyote meetings. The following winter, an older Kiowa man I’d grown close to asked Horace to hold a peyote meeting to work with his grandson, who was suffering from a rare blood disorder. I was afraid he wouldn’t let me in, since non-Natives were often not allowed. Before the meeting, Horace stopped for a moment and looked at me, as though he knew something. Looking back, I'm sure he knew in that moment that I would later become his apprentice.

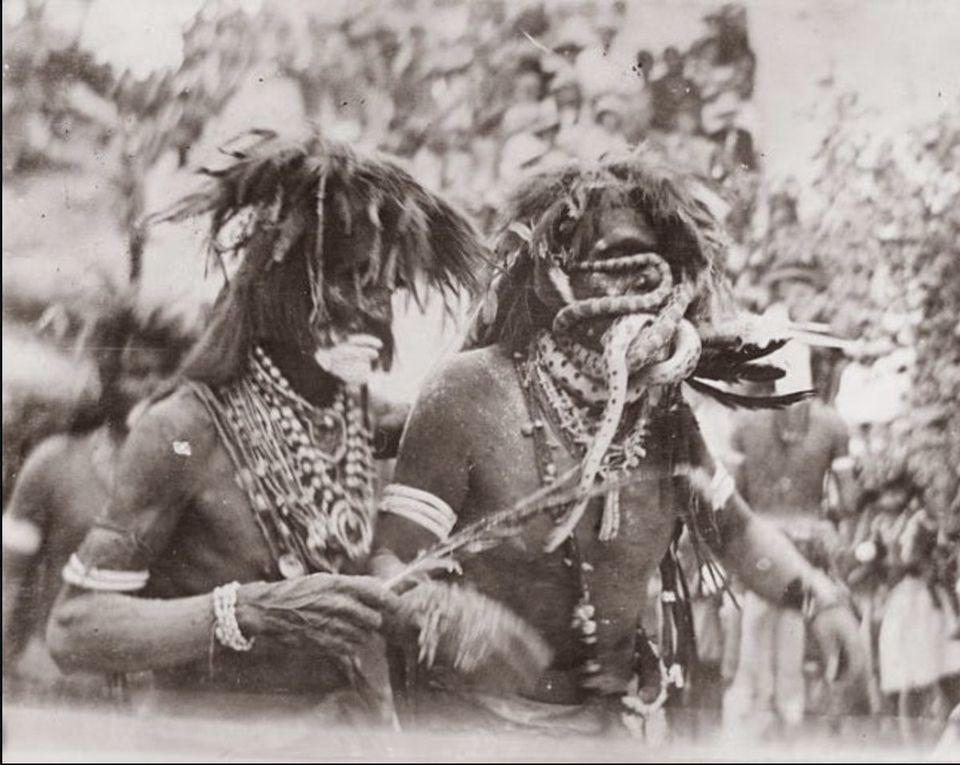

At sunset, we entered the tipi and took our seats. Sometime after midnight, Horace began to work on his patient. He first covered the body with a black silk handkerchief. Horace, like many traditional doctors over the centuries, possessed paranormal abilities. He took a live piece of coal from the fire and placed it in his mouth. As he blew on the coal, sparks flew from his mouth. He then had a live mole come from the ground and placed it on his patient to facilitate the healing process.

After speaking with a few friends, I decided to approach Horace. When I finally met up with him on a Friday evening, I was so fearful that he wouldn’t be receptive, and I was shaking as the words came out of my mouth: “I want to learn to do what you’re doing.” Horace responded, “What are you doing this weekend? Can you start fasting?” I immediately said, “Yeah, sure.” He then had me drive down to the Wichita Mountains and fast for the next two days without food or water to see if I was truly serious.

After my brief fast, I met Horace following a peyote meeting the next Sunday, as he had asked me to. We spoke for a while, and then he asked me to come out to stay with him at his home on the Navajo Indian Reservation where he lived with his wife in northern New Mexico.

Everything about my apprenticeship with Horace was intense. From the beginning, he took me along and had me assist as he doctored his patients. At times he would take objects, such as the end of a feather seeded with the medicine he possessed and then transmit portions of his healing gifts to me by projecting it into my body. Whenever he did that, it sounded like a gun with a silencer going off, and it would knock me briefly unconscious. Horace would then have me go through the vision quest, a native practice that involves fasting alone in the mountains for four days and nights without food or water to earn the right to work with these gifts of healing.

As I progressed, Horace had me take a more active role in assisting him with his patients. On one occasion he had me help with a man who was left paralyzed from the waist down after a front end loader turned over on him. I was stunned when I saw the blood clots that had come out of the back of the man’s leg.

At one point, Horace dropped me in the middle of the Hopi Indian Reservation with thirty dollars and my backpack, instructing me to hitchhike to Las Vegas, find work while I was there, and do the best I could to make it on my own. He expected me to tune in to my intuition to survive.

For nearly three years, I trained with Horace, who is still, to this day, the most powerful healer I have ever known or even heard of—especially when it came to assisting people with physical health–related issues. Despite his power and the extraordinary gifts of healing, he had never learned how to work effectively with his own emotions; therefore, his traumatic wounds hadn’t healed. There was a very reckless side to Horace, and when I saw he was becoming destructive, I severed ties.

Not knowing what to do, I flailed on my own for a time, then gradually started working with people. At the same time, I found myself reenacting the traumas of my childhood and adolescence. That led me to develop my own system of meditation—practices that activate the innate healing intelligence residing within the body and mind. I was also exploring any therapeutic modality I came upon that held promise. And in 1993, I began returning to the Wichita Mountains to go on the vision quest, and I’ve gone back every spring and fall since.

So Much Has Been Lost

Shortly after arriving in Oklahoma, my friend Steve introduced me to his adoptive father, Jack, who at that time served as president of the Kiowa Chapter of the Native American Church. While talking with Steve, I told him how much I wanted to go into the peyote meetings. Steve immediately said to his father, “Hey, Dad, Ben wants to go into the peyote meetings.” The Kiowa normally didn’t allow non-Native people to attend, yet Jack made an exception for me. When he got pushback from some of the other Native elders, Jack said, “This one is different. Let him come in.” Because the elders held a great deal of respect for Jack, they deferred to his authority. Over time, the elders began to warm up to me.

Initially, I struggled in the peyote meetings. My butt hurt, my back ached from sitting cross-legged all night, and I found it really difficult to stay awake. If I ate enough peyote, I’d be wide awake—yet with my sensitive stomach, I’d get nauseous and throw up—and those Kiowa folks, as much as they liked to gossip, were talking among themselves about my throwing up. Intuitively, I figured out that I needed to start ingesting the peyote in the early afternoon to give my body time to acclimate. As long as I did that, I could eat lots of peyote—and once I did, the meetings became a powerful experience for me.

It must have been a real head trip for some of the Native elders—here’s this white kid, me, still in high school, who just shows up on his own and sits up all night in the tipi with them. Meanwhile, their own grandchildren, nieces, and nephews didn’t give a damn about any of this—they were off partying, running around, or watching television. It must have been an even bigger trip when I took off to train with Horace, one of their last surviving traditional doctors. Some of the younger folks would say, “Damn—you’re more Indian than we are.”

After my friend Steve shipped off after joining the army, I ended up spending an enormous amount of time with his father, Jack. I was in my late teens and Jack was in his late sixties, yet I thought of him as one of my best friends. Jack’s health was declining, but I would still attend peyote meetings with him on occasion. I also helped with mowing and other housework that needed doing. We spent many evenings at the kitchen table as I listened to Jack recount stories of his life, his Kiowa people, and their history.

What fascinated me most were the stories Jack shared about the traditional Kiowa doctors (medicine men and women), the powers and paranormal abilities they possessed, and the vision quest. I would sit for hours in rapt attention, listening to him recount these stories. Yet Jack held a view common among many of his Kiowa people—that this medicine power would only work for those born Native. That’s part of why I disappeared for some years when I went off to apprentice with Horace: I didn’t want anyone telling me what I couldn’t do. The last time I ever saw Jack, I was with Horace, and we stopped by his house. At one point, Jack looked at me and said, empathetically, “We miss you!” At that time, I was still carrying a lot of trauma and was so dissociated; I didn’t fully register how significant he was to me. I often wish I could sit with him again and talk about all I’ve experienced.

In times past, there were many extraordinarily powerful Native doctors, many possessing paranormal abilities. Some could extract fluid from the lungs of someone with pneumonia or remove a bullet or arrow from the body of someone who had been wounded and then close the open wound. Others could bring rain in times of drought or change the course of a tornado heading toward their encampment. And then there were those who carried what was called “war medicine.” The enemy would shoot at them in battle, yet they came out unscathed. I’ve heard these accounts from Jack and numerous other elders on many occasions, and some had witnessed firsthand the miraculous healings performed by these doctors in their younger years.

What really saddens me is how much has been lost. Native children were taken from their families and forced to attend government- and church-run boarding schools—sometimes thousands of miles from home. They were beaten for speaking their languages, shamed and humiliated for their heritage, and, in many instances, subjected to verbal, physical, and sexual abuse. Some died while in these schools… resulting in generations of Native children who were deeply traumatized. Many, once they returned to their people, wanted nothing to do with their traditional practices.

The United States government forbade Native people from practicing the Sun Dance and other ritual practices, so Native communities took them underground. With each passing year, the traditional doctors were getting older. Many realized their profound gifts of healing would be lost forever unless they were passed on. They wanted desperately to pass their medicine to a younger apprentice, but in many instances there was no one willing to receive it. Sadly, many of these doctors took their medicine—the powerful gifts of healing—to the grave.

Another issue: the younger generations are often not willing to undergo the vision quest—fasting alone in the mountains for four days and nights without food or water—the Sun Dance, or other ritual practices. They’re not willing to accept the responsibility that comes with carrying these powers. They’re more comfortable living with the conveniences of modern-day life. Consequently, so much of the beauty and power that was once an integral part of Native life has died out.

Presently, there are very few Native doctors left. You can still find some among the Lakota, the Navajo, and some of the other Western tribes, yet they’re nowhere near as powerful as those in times past. A few years ago, I saw a man who had suffered severe head trauma after a vicious assault. He had been treated by a Lakota doctor, but I didn’t see much improvement—he looked terrible. After I worked with him, he responded quite well and showed significant improvement.

Weekend Workshop Healers and Instant Shamans

One of the things I hate most about New Age spirituality is how it trivializes and commercializes ancient traditions and practices—go through three weekend workshops and now you’re a master healer… or now you’re a shaman. It’s profoundly ignorant and misguided. The fact is, the people offering these trainings—and the ones taking them—do not possess any real power or capability. I’ve told people, “Stop calling yourself a shaman. Stop calling yourself a healer. Because you’re not.” You’re no different from a child playing doctor with a toy stethoscope.

I’ve asked many, “How would you feel if you needed dental surgery or other critical medical intervention and then learned your ‘dentist’ or ‘physician’ had three weekends of training?”

Native Americans and other Indigenous peoples knew who their traditional doctors were and understood the powers they possessed, because these things have been part of their cultures for thousands of years. The problem is that most people in our modern world have never had any contact with traditional Native doctors, or with adepts from other ancient spiritual traditions, who actually possess these powers. That’s why people today have absolutely no point of reference. In fact, many traditional Native doctors would literally scare the shit out of most people now. These individuals operate on a completely different plane and possess extraordinary abilities, and those powers will trigger people who aren’t used to them.

In every ancient tradition I’m familiar with, becoming a healer is an extraordinarily arduous, years-long process. In the tradition I trained in, you typically apprentice with an older doctor toward the end of his or her life, who transmits all or a portion of their power to you. You’re then expected to go on the vision quest—fasting alone in the mountains for four days and nights without food or water—to earn the right to work with these gifts of healing. And if you're truly serious, you'll keep going through the vision quest.

Traditional Native American doctors—and other Indigenous healers—typically take on only one, or at most a few, apprentices, usually toward the end of their lives. They certainly don’t accept whoever shows up with money. Passing the medicine to too many people dilutes the power and pollutes the lineage.

So when people ask how to become a healer, I tell them: forget the weekend workshop bullshit. Go to the parts of the world where Indigenous healers still exist. If you were studying modern medicine, you’d relocate to attend medical school and dedicate years to rigorous training. Similarly, if you truly want to become a healer, you’ll probably need to live with—or be in close proximity to—the doctor for years. That’s the path. Not three weekends and a certificate.

So Where Can I Actually Find One of These Doctors or Shamans?

Sadly, as I’ve pointed out, so many of these spiritual traditions, practices, and the extraordinary gifts of healing and other powers are being lost. There are still some intact traditions and places in the world where they exist—although even these are being diluted. In India, for instance, many within the Hindu-Vedic tradition still carry a great deal of knowledge and power. Even there, though, many gurus are not what they once were. Too many are now embroiled in corruption and scandals, and much of it feels cultish.

The Tibetan Buddhists have suffered enormous upheaval with China’s occupation of Tibet and the forced exile from their homeland, yet in many respects they’ve maintained the integrity of their spiritual tradition. Some teachings are probably diluted to make them more accessible to Western followers, but they still have a great deal to offer and provide a viable path for those who genuinely want to grow spiritually.

As for medicine men and women—or shamans—you may still find some among certain Western tribes such as the Lakota and Navajo. But it’s probably not going to work for you show up and say, “I want to be your apprentice. Will you teach me?” You’ll likely need to live in the community, or at least spend significant time there. You have to actually build relationships—a process that takes time. It’s also important to be on the ground—become intimately familiar with the culture, practices, and people involved—so you know what you’re dealing with. You may find others in some of the more remote tribal communities in Canada, although these practices are dying out there as well.

Many of the Indigenous tribes in parts of Brazil, Ecuador, and other South American nations were able to maintain their culture, traditions, and practices much longer because of limited exposure to Western influence, although that is changing rapidly. That said, traveling into remote territories to “find” healers is neither safe nor ethical. Some communities actively defend their lands, and outsiders who trespass can be harmed—or worse. Just as serious, uncontacted or minimally contacted tribes are highly vulnerable to common illnesses; pathogens like measles or influenza can be deadly. In many regions, contact is restricted or illegal for exactly these reasons.

Brazil does have a long tradition of gifted non-Indigenous healers, particularly in regions such as Bahia. The Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia have long-established healing traditions, many of them are extraordinarily powerful.

The use of ayahuasca and other hallucinogens has become increasingly popular in recent times; you may have powerful visionary experiences, but you’re not going to develop extraordinary powers or gifts of healing from attending these ceremonies. In Mexico, there is traditional use of psilocybin, but I haven’t heard of any truly powerful healers.

Not only have ayahuasca and other plant-medicine ceremonies become commonplace; they’ve also become a huge money-making business—running into the hundreds, even thousands, of dollars a pop. I never paid money when I attended peyote meetings; I brought food, helped gather firewood, or helped set up the tipi.

Another important consideration: when you ingest a substance like ayahuasca, your natural protective boundaries come down. You’re more open, more permeable. In a small, enclosed space, that permeability matters. If someone in the circle drinks heavily, uses other drugs, mistreats animals, children, or anyone, is manipulative or chronically dishonest, or is otherwise dysfunctional and toxic, acutely or chronically physically ill, or experiencing psychiatric issues, you’re more likely to take on their garbage.

There are shamans among the Hmong and other Indigenous groups of Southeast Asia, and among the Indigenous peoples of Siberia. I don’t know much about the healing traditions across Africa, but I’m open—should I encounter any I get a good feeling about.

A Word of Caution

It’s good to be open, get out of our bubbles, explore, see what’s out there, but I do want to offer a word of caution. In some parts of the world, poverty, and locals who see no clear path forward, can create real risk: robbery, assault, kidnapping for ransom, even murder. You need to keep your radar up at all times when you travel. For women, there’s even greater reason for caution: just because someone possesses power doesn’t mean they have good boundaries or good intentions. Some use their position and power to seduce younger, attractive women. And among certain South American shamans, there’s a tendency to play both sides of the fence; they may use power to facilitate healing, yet also to inflict harm.

That said, there are wonderful experiences to be had. Traveling to these places and working with truly powerful healers can open whole new worlds. As I learned living among the Kiowa and the Navajo: keep your eyes open, keep your back to the wall, and tune in to your intuition. Vet people through the community, move slowly, set clear boundaries—and listen to your gut. When it says yes, take the next step.

When You’re Ready to Do the Work

If you still have questions, or if you want to pursue working with a healer—or even become one yourself—you’re welcome to reach out. I’ll share what I can. Please keep in mind that I work very long hours. If you’re asking for guidance outside a session, that’s time away from the work I do to support myself, so please consider making a donation.

Having trained with a traditional Native doctor of the Kiowa Tribe and gone through so many vision quests, I work as a conduit—allowing an extraordinarily powerful presence to move through me to facilitate healing in the body and mind. These sessions are especially helpful for people dealing with anxiety, depression, and trauma; going through a breakup or divorce; or struggling with attachment wounds. They also address a wide range of physical, health-related concerns, including digestive and respiratory issues, sports injuries, and injuries from automobile accidents—including traumatic brain injuries.

To learn more or schedule a session, call or message (332) 333-5155 or visit teachmetomeditate.com • benoofana.com.

©Copyright 2025 Ben Oofana. All Rights Reserved.

Leave A Comment